Be mindful of what will happen when interest rates rise, but note that rising debt levels in Canada are no reason to panic, at least according to Stephen Harper. Canada’s Prime Minister is quick to note that his wife and he are not overleveraged, and neither are the majority of Canadians. In fact, to listen to Mr. Harper speak, one would be hard-pressed to find that group of Canadians that he thinks have taken on too much debt and need to think about how their fortunes will turn if interest rates rise.

Be mindful of what will happen when interest rates rise, but note that rising debt levels in Canada are no reason to panic, at least according to Stephen Harper. Canada’s Prime Minister is quick to note that his wife and he are not overleveraged, and neither are the majority of Canadians. In fact, to listen to Mr. Harper speak, one would be hard-pressed to find that group of Canadians that he thinks have taken on too much debt and need to think about how their fortunes will turn if interest rates rise.

The world may be full of “lies, damned, lies and statistics”, but Mr. Harper should look at his own government-issued numbers to see which one he is guilty of.

Household debt to GDP in Canada is around 95%, higher than at any time in recent history. In fact, this statistic is up nearly 20% since the global credit freeze of 2008. Government debt is not doing much better. It too is higher than it has been for 14 years, and its current level of 85% of GDP is an increase of almost 30% since 2008.

Debt might be nice when economic conditions are strong and interest rates are low, but both these factors can change rather quickly. Just look at the Irish case. In 2008 debt levels were lower than they had been in at least a generation. Strong economic growth coupled with low interest rates made servicing this debt easy. The credit crunch which drove rates higher coupled with the onslaught of a recession imperiled the Emerald Isle and drove it to the brink of bankruptcy.

Indeed, Harvard professors Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff’s book “The Time Is Different” looked at eight centuries of economic panics and recessions and found a common underlying theme. They were almost all associated with high levels of indebtedness. In particular, debt levels – whether corporate, household or government – higher than 90% of GDP were usually associated with slower economic growth or outright recession. Canada seems to be on the precipice of this solemn future.

Maybe Stephen Harper is mistaken in his belief that the vast majority of Canadians are not in danger of a slow-growth future making these debts harder to repay. Or maybe he is lying. After all, the propensity to borrow money is determined in large part by interest rates.

Harper, serving as he does as Prime Minister of Canada, must be aware that the Bank of Canada which he ultimately oversees has held its key borrowing rate almost as low as possible for over four years now. As recently as 2009 the Bank had driven down its prime discount rate to a quarter of a percent. It has since softened its stance, but the rise to 1% is a far cry from any semblance of normality.

How do I know this you might ask?

On the one hand the demand for credit is higher than it has been in a long time, as evidenced by the growing levels of indebtedness in all corners of the Canadian economy. On the other hand the supply of savings is not especially large. Today the country runs a current account deficit of about 3% of GDP, which is down from a balance of trade as recently as 2008. This negative trade balance implies that Canadians are consuming beyond their incomes and in need of the kindness of foreigners willing to lend them money to make up the difference.

High demand coupled with low supply is a recipe for a high price, in distinction to the low interest rates we actually see in the economy.

One reason for this is that the Bank of Canada has been flushing the economy with money. As recently as 2009 the BoC increased the narrow money supply by nearly 15%, and the annual growth rate has fallen hardly below 10% at any point in the last decade. The tidal wave of cash that the Bank injects into the Canadian economy has to go somewhere, and bank lending is the ultimate destination. Easy credit for Canadian consumers has been the common outcome through the last decade, fueling a spending and borrowing binge.

Indeed, while the Bank of Canada controls the discount rate, consumer borrowing is also concerned with the effects of inflation. Prices for some big ticket items like fuel and housing climbing rapidly over the past few years have brought price inflation higher than the cost of borrowing.

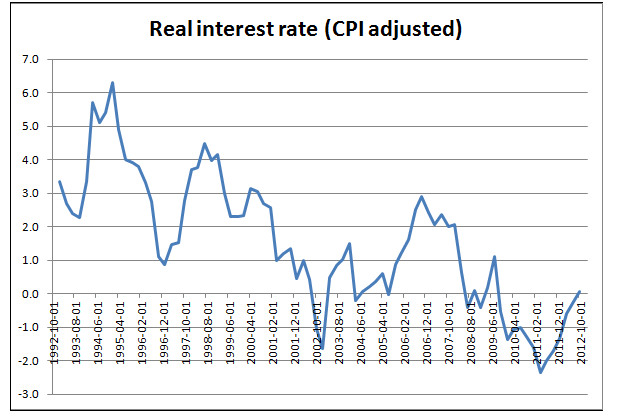

When a consumer borrows, he is concerned with the real interest rate. This measures how much he will have to pay back once the effects of the lost purchasing power of his dollar are accounted for. Once we adjust the BoC’s discount rate for inflation we see that borrowers got a free lunch over the past four

years. A negative rate implies that you actually earn money by borrowing money! Since the value of the dollar falls faster (due to inflation) than the increase in the amount you will have to pay back (due to the Bank of Canada controlled interest rate), you will be paying back less money in the future than you borrowed today.

Any rational person would do exactly what Canadians have done over the past decade: borrow and spend! After all, the more you borrow the more money you make. That is, until the bills come due or interest rates rise.

When Prime Minister Harper laments that some Canadians need to get their personal finances in order and warns that everyone should prepare for rising interest rates, he is signaling the end of this easy money environment. This warning is commendable. (It is, after all, no different than my own motivation for writing this article.)

But rather than just warn borrowers about the dangers of rising interest rates on their ability to repay their debts, why doesn’t the Prime Minister do something about it? Had the Bank of Canada not pushed interest rates so low over the past few years, the propensity to borrow amongst Canadians would not have been as great as it was. Mr. Harper could save himself the trouble of issuing a warning in the future by doing away with the problem in the present. Getting the Bank of Canada to pursue a sound money policy and not flush the economy with its tidal wave of cheap credit would go a long way in ending the madness.

Facebook

YouTube

RSS