Did the government of Canada use the Bank of Canada to fund World War 2 with interest-free loans? It’s a claim that is often made by the Canadian Greenbackers (or Loonies, as I like to call them). The Loonies maintain that, since the BoC is a Crown Corporation, it is essentially “our” central bank and that “we” can loan ourselves paper money to fund infrastructure and government services. It is often asserted that the government used this central banking function from 1934 to sometime in the 1970s. My research shows that it stopped in 1967. And it’s not as cut and dry as the Loonies maintain. The BoC under James E. Coyne (1955-1961) didn’t rely on this function. Coyne was adamant about using domestic savings to increase economic output. Most central bankers are content with importing savings from abroad (as well as creating inflation). The Loonies reject all this and demand the Bank of Canada make interest-free loans to the Government so they can spend without worrying about creditors.

Did the government of Canada use the Bank of Canada to fund World War 2 with interest-free loans? It’s a claim that is often made by the Canadian Greenbackers (or Loonies, as I like to call them). The Loonies maintain that, since the BoC is a Crown Corporation, it is essentially “our” central bank and that “we” can loan ourselves paper money to fund infrastructure and government services. It is often asserted that the government used this central banking function from 1934 to sometime in the 1970s. My research shows that it stopped in 1967. And it’s not as cut and dry as the Loonies maintain. The BoC under James E. Coyne (1955-1961) didn’t rely on this function. Coyne was adamant about using domestic savings to increase economic output. Most central bankers are content with importing savings from abroad (as well as creating inflation). The Loonies reject all this and demand the Bank of Canada make interest-free loans to the Government so they can spend without worrying about creditors.

Austrian economist and historian Gary North has a well of information about the Greenbacker ideology. For an overview of the Canadian position, see one of my previous entries. For the rest of this post, I’d like to focus on the WW2 myth being propagated by the Loonies (followed by some economic illiterate statements made by William Krehm).

For the first twenty-two months of WW2, the Bank of Canada acquired $1.9 billion of government securities. Unlike bonds, these securities matured in the short-term. They did not pay interest prior to maturity, instead being sold at a discount of the par value. Essentially, the Bank of Canada was buying zero-coupon bonds from the Government of Canada (but with some key differences). In a nut shell, the BoC advanced money to the federal government by holding short-term securities. The government then financed the first twenty-two months of WW2 with this money.

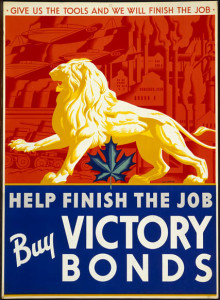

But the Loonies have skewed vision of history, as well as economics. This method increased the money supply, causing inflation. Thus – just as in World War 1 – Victory Bonds were introduced to remove money from circulation and to finance the war. A massive propaganda campaign and auctions where the government was the only legal seller made the Victory Bonds a success. Half the war’s expenditures were financed this way. The prior method of creating money and loaning it to the government “interest-free” created inflation and would have depleted the efforts essential to fighting the war. Of course, “interest-free” is ambiguous. Any interest paid to the Bank of Canada reverts to government coffers.

This is essentially the Loonie argument – paying interest to creditors is wrong when we can just loan the money to ourselves interest free. As COMER (the Committee on Monetary and Economic Reform) writes, after WW2 “Canada increasingly had to resort to borrowing from the private banks and other private moneylenders, including foreign sources.” This is because, quite simply, there is no such thing as a free lunch. Savings are required to finance capital projects. Interest is a product of time preference, i.e. $100 now is different from $100 in the future. If I loan you $100 now, I have to go without it. It only makes sense that I would charge you, say, $10, for giving you the money now in hopes that I get it back ten months from now. I take the risk. Now, what if I have a printing press and a coercive monopoly behind me? Well that’s problem with government, not interest. The Loonies don’t follow their reasoning far enough; they support giving the central bank and government more powers.

My sources for this post come from a book by William Krehm, the co-founder of COMER. As you can see, the Loonies don’t understand economics. I was able to take the same facts about WW2 financing and show why what Krehm tries to prove can’t be so. And this shouldn’t come as a surprise. Krehm’s economic reasoning is founded on his mathematical background. In addition he doesn’t like the word inflation because it implies “deflation,” which, according to Krehm, isn’t always the case. Instead, he uses the term “structural price increases.” It’s little wonder that Krehm promotes the inflationary policies he does when his whole understanding of economics is confused. Take this excerpt for example,

A prosperous economy generates private savings, encouraging individual Canadians to purchase government securities. Should inflation resume, excess purchasing power can be diverted by means of compulsory loans that would come into effect in targeted sectors. This in turn would provide a cushion of potential purchasing power to avert future recession. [pg 28]

Since this post is about financing WW2, I’ll leave Krehm’s nonsense for another day. Or for readers to comment below. Seeing as my last post on Loonies caused a bit of a stir, maybe any pro-Loonies out there can explain to me why I should take Krehm’s book (or COMER) seriously.

Facebook

YouTube

RSS